158 Steps Debuts in Hollywood: A Stirring Ode to Latin Theater and the Immigrant Experience

Renato Fimene brings a powerful monologue on identity, art, and belonging

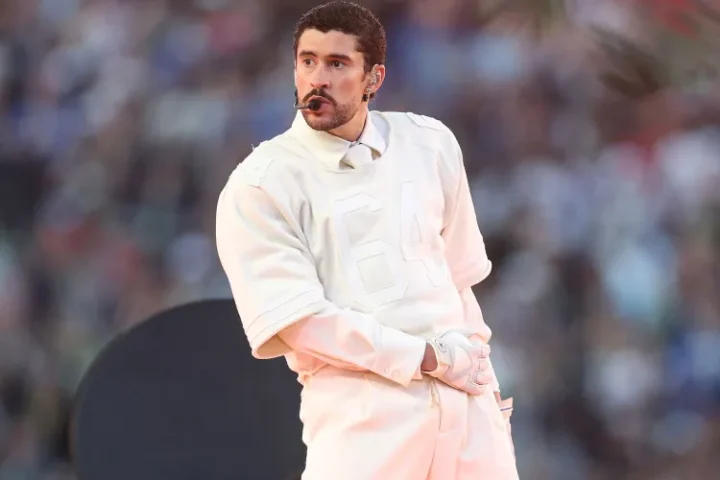

Hollywood, CA — In a city celebrated for its cinematic dominance, it was the intimacy of live theater that captured hearts on July 17th. The premiere of 158 Steps, a solo performance by Brazilian actor Renato Fimene, marked a significant cultural moment for Latin theater and immigrant storytelling in Los Angeles. Directed by César Baptista with visual collaboration from Thiago Roma, the production opened at The Artisans Creative Spaces to a full house and resounding praise.

Performed in Portuguese, English, and Spanish, 158 Steps is a poetic monologue that explores the intersection of art, identity, and survival in an America grappling with its immigration narrative. It tells the story of “Nobody”—an unnamed immigrant artist navigating the spaces between visibility and erasure in the world’s entertainment capital. The play draws inspiration from Homer’s Odyssey, where Odysseus calls himself “Nobody” to survive—but at the cost of losing identity.

Exclusive Interview: Behind the Scenes of 158 Steps

1. Renato, what inspired you to bring this deeply personal story to the stage – and why now?

I think this story had been quietly living inside me for a long time – growing in the background, shaped by moments of silence, confusion, and reinvention. As an immigrant, an artist, and someone constantly shifting between languages, cultures, and expectations, I found myself carrying a weight I didn’t always know how to name. The pandemic intensified that feeling – it paused everything, stripped away distractions, and forced me to confront who I was becoming. Around that time, I was navigating career changes, grief, distance from home, and the quiet but relentless negotiation of identity in a place that often wants to flatten or erase complexity.

But I also realized I wasn’t alone. So many of us – immigrants, outsiders, people in translation – walk through life carrying stories that don’t fit neatly into one language, one country, or one version of self. 158 Steps became my way of honoring those stories. It’s deeply personal, yes, but it’s also a mirror. A space to say: I see you. I’ve felt that too.

And why now? Because I believe this moment demands it. We’re living through a time of intense polarization, where immigrants – especially artists, storytellers, and those who live between borders – are often seen as threats or burdens, instead of contributors to the cultural fabric.

This project would never have come together without the fundamental creative partnership with César Baptista and Thiago Roma. César directed many of the plays I participated in back in Brazil – most of them impeccably and recognizably written and directed by him – and Thiago, who is my favorite Director of Photography, started working with him on my last film, SNAIL, which tells the story of a man facing homelessness in Los Angeles. Over these last months, they traveled from Brazil to Los Angeles, and we walked side by side – intensely – facing every challenge at every level, shaping the project as a whole. I have deep admiration for the work they do as artists and am proud to be tied to such great human beings as they are. Their vision, dedication, and trust were essential to making this work honest, brave, and fully realized. Together, we turned a personal story into a collective act of resilience and storytelling.

I finally had the courage – and the collaborators – to tell it honestly. And I believe audiences are ready to listen, to feel, and to be challenged in a deeper way.

2. César, how did directing remotely from São Paulo shape the creative process and the final performance?

This project has been managed for a long time, but I immersed in the universe of the play, from December last year, when Renato and I talked to carry out the idea.

From there, I began the process of writing the text, based not only on Renato’s experience as an immigrant, but also that of other artists and, above all, of people who live and lived in this condition, through documentaries, books, news, reports and testimonies.

I’m used to writing and directing my own texts, this is not the first time. Usually, I separate the two functions well and try not to let my director side interfere with my writer side. However, in the process of 158 steps, as I knew we would have less time to rehearse than we would like, in the very writing of the text, I have already been thinking as a director.

Until my arrival here, in early July, Renato and I had weekly meetings and readings, through which Renato and I established directions on how I understood his performance would be, for example, in the middle of the process, we decided that it would be better for his performance, if he adopted a storyteller posture for the routing of his interpretation and so on. But, yes, of course, the scene markings, movements and even changes and cuts in the text were made when I arrived here for the face-to-face rehearsals.

Many of these changes also happened because of the dialogue between theater and audiovisual. I imagined that this interaction could contribute to the relationship between reality and fiction, and the dialogue with Thiago was very fruitful in order to enhance this relationship. With this, we managed to make the narrative plan of the audiovisual not merely illustrative, but rather that it played with the limits, with the borders, with the walls and bridges, because, ultimately, that’s also what the play is about.

3. Thiago, your creative collaboration added visual and emotional depth to the monologue. How did you approach the narrative’s visual language?

Cesar had some initial ideas in the script for what the projections could be in each scene. But once the three of us started working together, we ended up reimagining everything from scratch. That collaborative process, where each of us brought our own perspective and kept challenging ideas, is what I think gave the projections real emotional and narrative weight.

Right from our first online meetings, we were all very clear: the projections couldn’t just be something decorative or simply illustrative. We treated them almost like another character on stage – one that could help move the story forward and get the audience to places the stage alone couldn’t physically or metaphorically go.

Looking at the result now, I’m honestly proud. I think we managed to create a visual language that’s fully part of the storytelling and brings an extra layer of meaning to the monologue.

4. The protagonist being named “Nobody” is a profound metaphor. Can you expand on the decision behind this identity – and its symbolism?

The name “Nobody” is a deliberate reference to The Odyssey, where Odysseus, in a moment of survival, tells the Cyclops that his name is Nobody – so when he fights back, his cry for help is dismissed. It’s a brilliant act of self-preservation, but it also comes at a cost: erasure. That duality felt incredibly resonant for me. As immigrants, as artists, as outsiders, we often wear this invisibility as a form of protection. We code-switch, shapeshift, dilute ourselves just enough to pass unnoticed or unthreatening. We’re told, subtly or directly, that to belong we must disappear a little.

Naming the character “Nobody” was a way of honoring that tension – the survival strategy and the internal fracture it creates. It’s a name that hides, but also resists. It says: If I have to be Nobody in your eyes to survive, then I will take that name – and turn it into something that speaks louder than silence.

At the same time, it invites the audience to question the systems that force people into invisibility. It asks: Who gets to be Somebody? Who defines worth, identity, voice? And for those who see themselves in that name, it becomes a quiet act of rebellion – because in telling their story, they are no longer Nobody. They are seen. They are heard.

5. Renato, as a Brazilian artist in Los Angeles, how does 158 Steps reflect your own lived experiences?

158 Steps is, in many ways, a reflection of my personal journey- geographically, emotionally, and artistically. It’s rooted in moments I’ve lived: walking into casting rooms and immediately sensing I was “too much” or “not enough” – too foreign, too ethnic, too expressive, too complex. I’ve often been asked to simplify myself, to soften my accent, to edit my identity into something more convenient or familiar. Those experiences linger. They accumulate. And they shape how you move through the world.

But the play also holds something else: a quiet defiance. It’s about reclaiming space and voice – not just for me, but for the many others who are told, explicitly or implicitly, that their stories don’t matter. As a Latino – and specifically as a Brazilian, which sometimes doesn’t fit neatly into the boxes of Latinidad in the U.S. – I’ve often felt both included and invisible. There’s so much richness in our cultures, and yet we’re frequently flattened into stereotypes or left out of the narrative altogether.

158 Steps is my way of refusing that invisibility. It’s a love letter to the resilience I see in my community – immigrants, Latinxs, artists, dreamers, people who keep pushing forward despite the noise telling them to shrink. It’s about holding complexity with pride. It’s about making space for our voices to be heard on our own terms. It’s me saying: I’m here. We’re here. And we’re not just background characters – we are the authors, the protagonists, the storytellers.

6. How has the audience reception differed across language-speaking communities – Portuguese, English, and Spanish?

What’s been most powerful is witnessing how 158 Steps transcends language while also honoring its limitations. The play moves across Portuguese, English, and Spanish – not just as a stylistic choice, but as a lived necessity. I exist in all three languages. And in that movement, something beautiful happens: even when audiences don’t understand every word, they still feel the emotion. That’s the paradox – and the power – of theater. It’s not just about comprehension; it’s about connection.

We chose to work in three languages not just to reflect my personal experience, but to explore how language actively shapes our perception of the world. Language can build bridges, but it can also create borders – between people, within cultures, even inside ourselves. It carries not just meaning, but memory, identity, and at times, deeply rooted prejudice. When we speak, we don’t just communicate – we reveal how we’ve been taught to see.

By blending these languages, we wanted to invite connection across communities, but also to make audiences sit with the discomfort of what gets lost in translation. And that discomfort is part of the story – because navigating multiple identities often means living in that space between clarity and misunderstanding.

The responses have been deeply moving. Portuguese-speaking audiences often express a rare feeling of being represented – of hearing the rhythm, the soul, the specificity of their language on stage in Los Angeles, where it’s so often absent. English-speaking audiences tend to connect with the emotional core of the story – the universality of identity, migration, and the search for belonging. Spanish-speaking viewers often recognize themselves in the fluidity, the code-switching, the cultural negotiation happening in real time.

But what unites all of them is the recognition that storytelling – real, vulnerable, multilingual storytelling – goes far beyond the words themselves. It’s about being seen. It’s about claiming space. And it’s about remembering that our voices, in all their complexity, matter.

7. What message do you hope viewers carry with them after watching 158 Steps?

I hope they leave with a sense of recognition – whether it’s something they’ve lived, something they’ve felt but never named, or something they’re just beginning to understand in others. Even though 158 Steps is rooted in personal experiences, it’s ultimately about the universal journey of becoming. It’s about identity, displacement, memory, and the quiet courage it takes to keep moving forward when the world doesn’t quite know where to place you.

More than anything, the play is an invitation. An invitation for each of us to take our own steps – whatever they may look like – and to reclaim authorship over our own narratives. To stop waiting for permission, or for the perfect conditions, to be the protagonist of our own story. The steps in the play is both literal and symbolic: it’s a passage, a reckoning, a daily act of choosing to keep going.

I also hope audiences feel the power of representation – of seeing themselves reflected on stage, or perhaps seeing someone unlike them portrayed with honesty, complexity, and dignity. Because representation isn’t just about visibility; it’s about belonging. And when we see a fuller spectrum of human stories, we remember that our differences are not threats – they’re invitations. Not walls, but bridges. Ways of knowing each other more deeply, and maybe even understanding ourselves a little better, too.

Backed by the American English Academy, with support from the Los Angeles Brazilian Film Festival (LABRFF), t.PR Agency, and the Consulate General of Brazil in Los Angeles, 158 Steps continues to run through July 27th at The Artisans Creative Spaces, 8 p.m. nightly. Tickets can be purchased at 158stepsplay.eventbrite.com, and more updates can be found at @158stepsplay.